Overview & Motivation¶

The “new golden age” of splintering computer architectures presents a new set of challenges for compilers. Where today’s compilers target fixed, slowly evolving ISAs, modern efficiency-oriented hardware changes rapidly to offer new domain-specific features and design parameter tuning with each release. This pace of hardware innovation is fundamentally mismatched to the traditional conception of an ISA as a stable, backwards-compatible abstraction. There are two (bad) options for designing traditional ISAs in the era of rapidly changing, domain-specific hardware:

- Hide the changes. A traditional ISA could try to fully abstract the differences in the underlying hardware models and to offer transparent, automatic efficiency benefits to existing software. While it would be convenient, full abstraction is probably impossible—it would require anticipating all possible hardware features in advance. And it would prevent higher-level programming languages and compilers from providing target-aware optimizations that rely on specific hardware details.

- Break the contract. Every new generation of specialized hardware could come with a correspondingly new version of the ISA. Using ad hoc extensions and changes, the ISA would expose all the important hardware details to the compiler—at the expense of backwards compatibility. If an ISA is a contract between hardware and software, every new generation of hardware would break the contract and offer a new one. This approach amounts to giving up on the idea of a long-lasting abstraction that persists across hardware generations, thereby foisting the responsibility for compatibility onto compiler writers.

HBIR is a third option. It acts as a meta-ISA, providing a consistent framework that unifies the members of a family of similar—but specialized—hardware. Each member of the hardware family gets its on specialized ISA, but instead of specifying the differences in an ad hoc way, the details of a specific machine are specified in an HBIR program. Higher-level software and toolchains can use HBIR as a systematic, consistent way to interact with specialized hardware.

By making the hardware target details explicit in a programming language, HBIR enables:

- Portable compilers that can customize code for new hardware capabilities without modification.

- Portable compiled programs that encode their assumptions about the range of supported hardware from the past and into the future.

- An experimental platform for designing new hardware iterations and examining their impact on software performance.

The end goal is a more fluid relationship between hardware and software. Intermediated by HBIR, architecture generations can evolve more quickly while software toolchains can more easily harness their new capabilities.

The Target Machine¶

The current realization of HBIR targets the HammerBlade manycore processor, which is a grid of simple RISC-V cores. The manycore tiles have instruction caches but no data caches, and hence no coherence—instead, cores have a local data memory that acts as a scratchpad. There is an on-chip network that lets cores read and write remote scratchpads.

The HBIR programming model primarily focuses on a SPMD style: the program describes similar code to run on collections of tiles. Each tile can use its index within a group to change the memory it computes on. This programming model is well suited to regular, dense data-intensive applications.

We have a prototype compiler for HBIR, called Lotus. It takes in an HBIR program and emits C code to execute on the manycore and an accompanying host processor. The HBIR program describes the size, shape, and capabilities of the HammerBlade hardware instance it targets. The generated C code is specialized to target this particular machine instance.

Design¶

An HBIR program consists of four segments that encompass the physical machine specification, a virtual configuration layer that abstracts the physical resources, and software—data and code—that runs on the configured virtual machine.

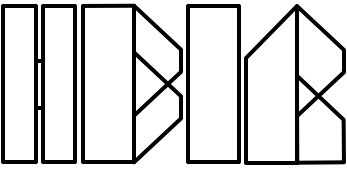

[This section needs a little expansion, and probably a diagram.

It’s our chance to describe philosophically what’s going on with each of the four segments, instead of specifically what the language looks like.

Namely, we need to get across the idea that the config segment acts as an intermediator that completely abstracts away the machine specification in target.]

Future Work¶

While HBIR currently focuses on static, SPMD, general-purpose manycore programming, there are a few big challenges that represent next steps for the abstraction:

- Incorporating accelerators. Aside from the homogeneous fabric of general-purpose cores, we imagine more customized iterations of HBIR will include fixed-function logic and communication structures. We want the HBIR machine model to incorporate arbitrary accelerators so software can transparently target them on targets where they are available.

- Dynamic reconfiguration. The configuration in HBIR is entirely static—it is fixed for the entire duration of a program. In the future, we want to use the same abstraction for configurations while letting them change at run time, in response to changing data characteristics and workload phases.